Red Alert: Danger in 2025

As we look ahead to 2025, it's critical to understand the risks associated with the sharp rise in concentration among major U.S. equity indexes like the S&P 500, Russell 3000, NASDAQ Composite, Russell 1000 Growth, and Russell 1000 Value. These indexes are increasingly dominated by the same top ten stocks by market capitalization—household names such as MSFT, AAPL, GOOG, AMZN, NVDA, META, TSLA, BRK, UNH, and JPM. This trend has left retirement portfolios—including 401(k)s, IRAs, pension funds, and individual investors—highly interrelated and exposed to a single market narrative. While the "Magnificent Seven" stocks propelled index returns in 2024, we’re now seeing troubling signs: their market caps far exceed forward revenue and earnings growth, their valuation premiums appear unsustainable, and their return on capital employed (ROCE) appears in decline. As ROCE weakens, valuations typically follow. At this point in the market cycle, we strongly advise against holding any large market cap-weighted index-based investments like the S&P500. We prefer the risk-reward profile of the Russel 2000 index, as small-cap stocks appear to be undervalued. This is seen in the chart below, Russell 2000 vs S&P500.

In our view, 2025 could mark the beginning of a significant unraveling of this trend, making active portfolio management more critical than ever. As Howard Marks emphasizes in his book Mastering the Market Cycle, "the odds change as our position in the cycle changes."

Let me illustrate the danger discussed above with two charts presented at the Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder meeting in May 2021. On the left were the 20 largest companies by market capitalization (MC) in 1989, and on the right, the 20 largest in 2021. The first striking observation is the absence of 1989's "hot stocks" like IBM, GE, Exxon, and Merck in the 2021 lineup—echoing the fate of the Nifty Fifty stocks that eventually fell out of favor. The composition of the 2021 list is vastly different, dominated by U.S. technology companies. Moreover, the scale of valuations has ballooned dramatically: in 1989, the largest company had an MC of $105 billion, a figure dwarfed by the smallest company in 2021, which stood at $336 billion. This highlights a critical lesson: a great company does not necessarily make a great stock. Exceptional growth is hard to sustain, and valuations matter. History shows that when a narrow group of stocks drives the market, subsequent returns often disappoint investors.

At my 20th Harvard Business School reunion, a presentation highlighted a striking chart that underscores the scale and potential risks within today's financial markets. The Top 6 US tech companies collectively represent a staggering market capitalization of $15 trillion—an amount rivaling the GDPs of major economies, falling just below the United States' $28 trillion and China's $18 trillion. This concentration of value brings "danger" to mind, particularly when considering the heavy reliance of US Large Cap Mutual Funds and ETFs on these stocks. With passive investment strategies dominating the market, it raises the question: who is actively thinking? Such strategies operate on autopilot—a mental state where actions are performed without deep consideration, including investment decisions. This lack of scrutiny amplifies exposure to loss, introducing significant risk into the market landscape.

We take an active and deliberate approach to investing, modeled after Warren Buffett’s philosophy of buying stable, high-quality businesses and holding them for the long term. Unlike passive strategies, our framework is built around five key variables: book value, margin of safety, intrinsic value, current market price, and transaction value. Over the years, your portfolio has focused on bank stocks, given their stability, alignment with economic growth, and resistance to disruptive trends. Banks offer consistent earnings, low risk, and healthy dividends—an essential source of income for retirees.

Our investment process begins with book value, representing the per-share value received if the business were liquidated today. We emphasize a margin of safety, the gap between the purchase price and either book or intrinsic value, ensuring a favorable risk-reward profile. Buying banks below book value creates this essential buffer. Intrinsic value is calculated using fundamentals like deposit base, insider ownership, branch locations, and book value. While current market price—the most recent trading price—is often a meaningless number to us, it does appear on client statements. Instead, we focus on transaction value, or the price a buyer would pay for a bank franchise, typically around 2.0x book value or more. This liquidity event underpins our strategy.

In summary, our disciplined approach of purchasing below book value, holding investments for 5-7 years, and targeting transaction values enables a low-risk, high-reward strategy. As small bank assets continue their upward revaluation and consolidation, we anticipate even more opportunities in the years ahead.

As we look ahead to 2025, several historical measures remain far outside normalized equilibrium, creating a heightened risk of a sharp market correction. The U.S. markets are in a highly vulnerable zone, and a significant surprise could be on the horizon. Why? Because irrational behavior cannot persist indefinitely. Many market participants in passive investment products may not fully understand what they own but remain fully invested, clinging to the hope that markets will always rise.

Meanwhile, the U.S. faces concerning fundamentals, including high debt-to-output ratios, a massive trade deficit, and the prospect of a slowing global economy. The US Treasury’s annual interest expense surprased $1.1 trillion this year, making it the second-largest government expense. At the current issuance schedule and interest rates, it will surpass Social Security at $1.4 trillion in 2025 becoming the largest government expense.

The long bond (10-Year T-Bond) has gone from 3.99% to 4.5% in a short period of time. We believe inflation is far from over, with cost-push pressures likely to intensify in 2025, as evidenced by recent labor agreements. Examples of such increases are a 62% pay raise for Philadelphia dockworkers and a 38% raise for Boeing workers in 2024. This type of Inflation is hard to eliminate as it gets baked into the system for future years. Furthermore, Inflation erodes asset values by increasing prices while assets stagnate or decline.

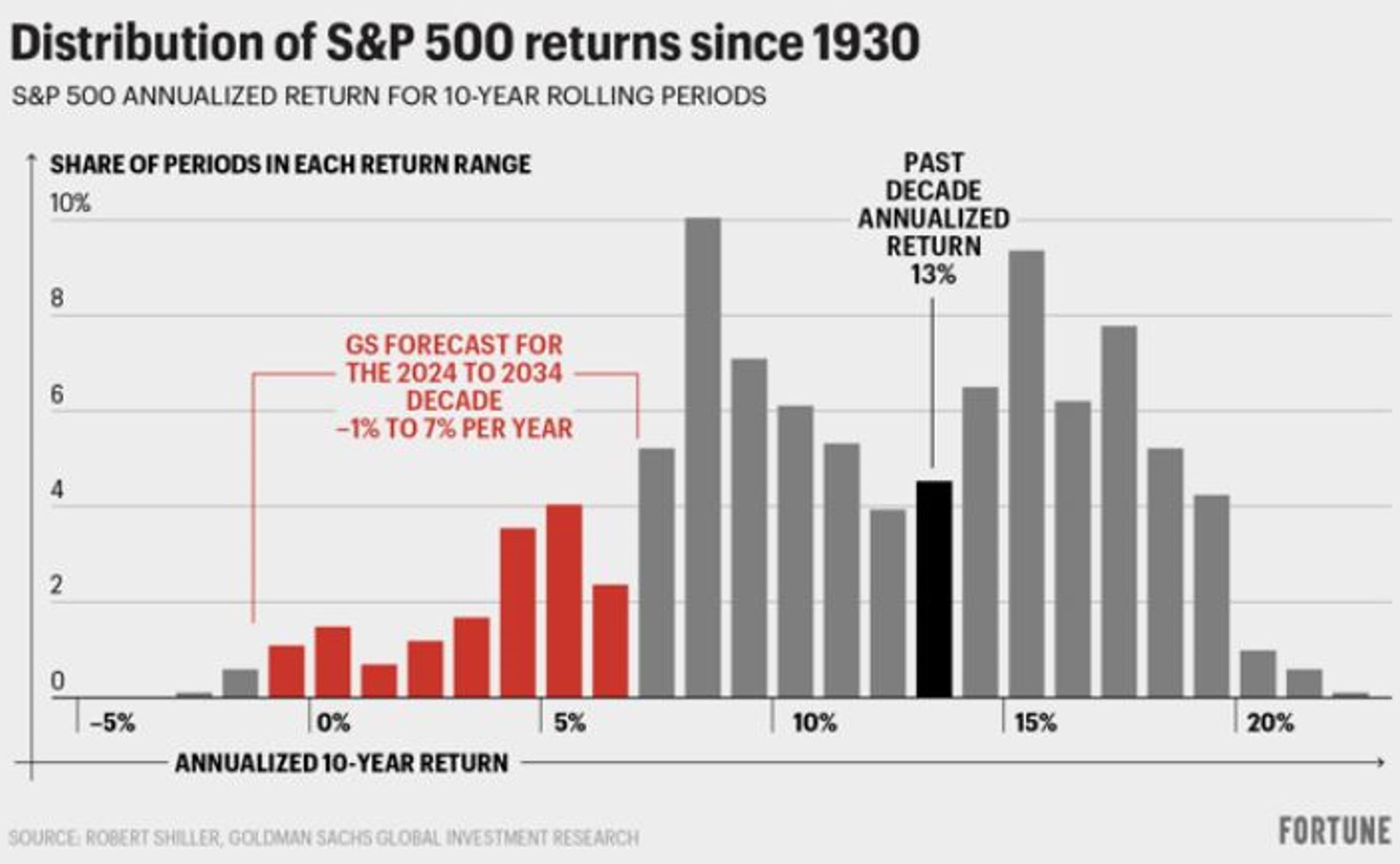

Finally, Goldman Sachs' October 2024 research warns of lower equity returns over the next decade relative to bonds and inflation—a perspective we find aligned with our view of the market environment.

Thank you for your continued confidence. Please feel free to call if I can be of further assistance to you.

Respectfully,

Dr. Christian Koch, CFP®, CPWA®, CDFA®, RICP®